In the Basque area on the borders between France and Spain: an anthropological fresco of the socio-cultural changes post-Schengen and the stiff resistance to communication brought about by cultural and linguistic barriers

“We no longer have the frontier blocking us. Now we can move around as freely as we want. But still, I don’t feel we have stronger relations with people on the other side.” Woman of Spanish nationality shopping on the French side.

“The frontier was once an obstacle; this is no longer the case. But now this is another challenge”. Man of Spanish nationality, ex-customs officer and now employee of a gas station on the Spanish side.

“I feel we used to have much more in common with people on the other side. Young people for instance used to hang out with each other, go to the fiestas across the border, however difficult it was. But now… It’s more each to one’s own.” Man of French nationality, mayor of the French Basque village of Arnéguy, and employee in a butcher’s shop on the Spanish side.

“Even though we all live in the Basque Country, there is a lot that separates us from our neighbours in Spain. We have different tastes and ambitions. I feel this gap has got larger.” Woman of French nationality, farmer in a neighbourhood of Arnéguy which, according to an old tradition, shares its parish with Valcarlos, the neighbouring village on the Spanish side.

These quotations come from conversations held in January 2007 with four inhabitants of the border between France and Spain in the Basque Country. These four inhabitants have lived a significant part of their life in the area, and all of them have in some way been affected by the opening up of the frontier.

As a result of the removal of border controls within the EU due to the Schengen agreement, many communities located in border zones have had to reassess their relationship with their neighbours across state frontiers. The Franco-Spanish border in the Basque Country is one of these cases, where numerous cross-frontier initiatives have been launched over the last decade. An increasing number of inhabitants now cross the frontier on a regular basis. In parallel, numerous economic changes have taken place, of which the steady urbanisation of the border is a consequence. All this means that traditional identities are altered with new emerging symbolic references.

We now ask ourselves whether we can find a corresponding opening up of local mentalities. The comments made by our four inhabitants indicate the contrary. While all of them are familiar with Basque, the language spoken on either side of the frontier, and with Spanish or French, the language spoken across the frontier, and most of them have family and friends on both sides of the border, they do not confirm a further rapprochement with each other. The opening of the frontier in effect only means the dismantling of border controls. Free mobility across the frontier, and EU-funded projects designed to foster cross-frontier cooperation have, so far, had limited influence on encouraging further mutual identification between border inhabitants who place increasing emphasis on their own identity The frontier remains an undeniable presence in ways of thinking and behaving.

Since 1999, the municipalities of Hendaye, Irun and neighbouring Hondarribia have joined forces to create the Bidasoa-Txingudi consorcio, named after the river and bay around which they are located and which here serves as the demarcation line between France and Spain. This consorcio enables the three municipalities to work together on social, cultural and economic projects to reflect the new realities of life of border inhabitants. Many of these projects have so far been mainly of a symbolic sort, organizing cultural fairs, sports competitions, and publishing a new map featuring all three towns together. Even the name Bidasoa-Txingudi is now a commonly used term.

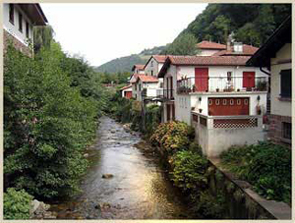

Further along the frontier to the east, in the mountainous region of the Basque country, the villages of Arnéguy and Valcarlos have more of a history of cooperation. Located only a hundred metres from each other and separated by a small river tucked in a narrow valley, farmers of the two villages have a centuries old tradition of sharing pastures for their animal herds. Valcarlos also traditionally shares its church with a neighbourhood of Arnéguy. Today, joint ventures are scarce, and no cooperation has been formalised. Currently, they are troubled by a project principally advocated by the region of Navarre, in which Valcarlos is located, to construct a motorway that would run through the valley. While most of the inhabitants of Arnéguy are against this, those of Valcarlos tend to favour it, disregarding its negative environmental impact, seeing in it an opportunity for easier access to Pamplona, the capital city of their region. Arnéguy, on the other hand, which continues to see its administrative relations in the French Basque Country looks the other way, and thus does not see the advantages of such a motorway. We see then that despite sharing a common space, inhabitants of either side use and perceive it quite differently.

In Bidasoa-Txingudi, meanwhile, while we notice the increased flourishing of businesses designed to attract the customer from across the frontier, it is not clear whether relations go any further than this. A television director in Irun for instance remains disillusioned; after his failed attempt to set up cross-frontier broadcasting with a partnership in Hendaye, he concluded, ‘cross-frontier cooperation just doesn’t exist really’. In local schools, cross-frontier exchanges are encouraged by the consorcio, but remain limited. This is due not only to institutional complexities but also because many parents remain unconvinced about the importance of further links with the language and culture of their neighbours.

It is revealing to note that on the border in the Basque Country, the occasions when a strong feeling of togetherness could be sensed was in moments of contestation. For instance, the Spanish governmental project to increase the size of the airport of Hondarribia was hotly opposed by a majority of the local population. We witnessed the inhabitants of the three towns demonstrating together, collaborating around this common cause, irrespective of their cultural and national differences. Another ‘other’ had emerged in the form of the threat of an airport enlargement.

In the period since 1993 many people have lost jobs that were directly linked to the existence of the frontier, such as customs officers, employees in state administrations and businesses that catered to frontier traffic. Most of the border controls have been pulled down, and the main roads linking either side of the frontier have been widened, adorned with new road signs indicating the name of the town and the European flag replacing any mention of state territory.

Today, new job opportunities are to be found in the services, tourist and property industry; new economies that have emerged but still in relation to the frontier. While border controls have disappeared, the frontier remains the demarcation of state control, and so with free trade and mobility new opportunities emerge. Many thought for instance that the ventas, so-called shops located by the demarcation line offering passers-by the last opportunity to buy national products, would disappear. Rather, ventas have become a great success, converted from modest shops into big commercial centres to which tourists flock, attracted by this last vestige of the frontier. Many local inhabitants now find employment in this highly lucrative business.

In Irun, the main town on the Spanish side, a large edifice has also been constructed over what until only recently was the train freight park where merchandise was inspected before crossing the frontier. This edifice is now an exhibition centre designed to host international commercial events. Another great change is in housing. In France, the relatively lower housing prices have encouraged the rapid construction of apartments which have for the most part been bought by people on the Spanish side. This has had the consequence of changing the demographics of the town of Hendaye, just a kilometre from Irun: Hendaye is now inhabited by a population of which just over 35% are of Spanish nationality (compared to 20% en 1999). Recently, another housing construction, managed by a Spanish business which only advertised its sales in Spain, provoked protest amongst Hendayans. They feel they are being overwhelmed by these new residents who still essentially live their social and cultural life on the Spanish side, where they also continue to have their jobs.

While border controls have disappeared, the beginning and end of a state territory remains visible in advertising panels, architecture and organisation of space. Modes of behaviour are different, as is even the way people perceive themselves as Basque. Although globalisation increasingly brings people to share more symbolic references and face similar concerns, their experiences remain translated by the particular institutional, political and cultural context in which they live. So the frontier remains in the mind. Identity exists in relation to an ‘other’. In order to have a notion of self, it is necessary to identify something that is different from oneself. Today with globalisation we find ourselves increasingly in a world where people have various origins and life experiences, and speak more than one language, and therefore have more complex identities. However, with the human tendency to want to order things, the clear categories of ‘us’ and ‘them’ remain tempting.

Globalisation is the new context in which cooperation and openness are a challenge. It is also paradoxical that it is the offer of financial support, for instance from the European Union, which spurs local actors to co-operate. For example, it is only since early 2007 that other border towns in the Basque Country have finally launched into cross-frontier collaboration. The president of the syndicate of the valley of Baigorri, next to Arnéguy and Valcarlos, declared then that, “we have the tools for cooperation, we now have to learn how to use them”, and recognised that “we will lose these funds if we do not organise ourselves in order to take advantage of them.” In this case, collaboration does not seem to come as spontaneously as it does in situations of contestation and urgency.

Today, cross-frontier cooperation projects are increasingly tackling the urgent problem of the environment and social needs. Such a more inclusive and long-term cooperation is positive. But for any real entente to take place it is necessary for inhabitants not only to learn to solve problems together but to get to know each other. It is noteworthy that all the informants for this article were aged over forty, and spoke at least two languages well. Amongst the younger generation this local multi-lingual fluency is rarer. With this reduced means of communication, the risk of alienation vis-à-vis one’s neighbour increases. It remains therefore to be seen how the younger generation of border inhabitants with their different linguistic capacities will construct their identity in this new context of so-called openness. x

Author of this story: Zoe Bray

Zoe BRAY is a social anthropologist currently specialized in the Basque Country and issues of nationalism and European integration. She has conducted research on identity politics in minority communities in European borders in affiliation with the European University Institute, Florence. Zoe is also a professional painter and illustrator. www.zoebray.net

Writer, translator and publicist with a degree in Pharmacy, he was a manager in the pharmaceuticals industry in Germany and Italy. Julius Franzot is bilingual (German and Italian) and was born in Triest, from where he works in support of Mitteleuropa through culture and politics.