From the first degree in Gorizia to the doctorate from Klagenfurt, passing through Ljubiana and Triest, a snapshot of Serena Fedel, at home in more than one univeristy of Alpe-Adria. Projects fors the future? That her children will speack the languages of the area: Slovene and Italian, not forgetting English and German obviously…

“My children will go to the bilingual nursery at Vermegliano, near Ronchi. At home we’ll speak Italian but it’s right that they should learn the languages spoken in the area from an early age, as much as it is that they learn German or English”. This sums up the project for a future euroregional experience of Serena Fedel, a citizen of Alpe Adria, who although a die-hard bisiaca (a speaker of the local Italian dialect), as she herself is at pains to point out, has lived for two years between Klagenfurt (in Austria), the Slovene capital Ljubljana, and Trieste

After being awarded a degree in Public Relations with top marks from the University of Udine 2002, Serena Fedel won a scholarship for a doctorate in Transboundary Politics in Daily Life: a creature born form the cooperation between the Institute of International Sociology of Gorizia and the Universities of Trieste, Udine, Klagenfurt, Maribor, Krakow, Budapest, Cluj Napoca, Bratislava and Catania.

“It seemed interesting to me to develop a project linked to the area of Alpe Adria. The theme came to me almost by chance through some publications I came across on a series of initiatives linked to the field of equal opportunities – she explains. I thought that a comparison between the conditions of women in Friuli Venezia Giulia, in Slovenia and in Carinthia could represent a new and still largely unexplored theme”. The results of the project were, on one hand, a doctoral thesis “Gender inequalities and social conditions of employed women in the Alps-Adriatic region. A comparison between Carinthia, Friuli Venezia Giulia and Slovenia, and, on the other an intense life and work experience, gained at first hand in the three areas; and, confirming the conclusions reached in her thesis – that Slovenia offers the best living and work conditions for women and recounts how it was in Ljubljana that, were she able, she would have stayed and lived.

“At the University of Klagenfurt there is a department dedicated to the promotion of Gender Studies, with a well-stocked library and, not of minor importance, my supervisor Professor Josef Langer. I did my first term of the doctorate there and, finding good working conditions, decided to stay on”. But the life of Serena Fedel at that time wasn’t only that of a student. Looking for alternate employment , more or less temporary, she worked as a barmaid and as a hostess at trade exhibitions – opportunities that on one hand allowed her to pay her way and on the other, “live” the city and practice the language, getting to know people. In the meantime there was a thesis to carry forward, in particular an analysis of the professional conditions of women, using a series of interviews with female employees of a bank with branches in all three areas.

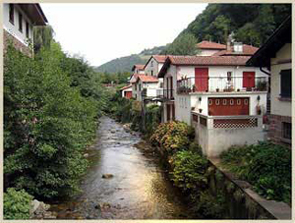

If fieldwork in the Region Friuli Venezia Giulia and in Austrian Carinthia could be completed fairly easily, the barrier of language was an issue in Slovenia. “I didn’t speak Slovene” she explains, “ and from my arrival in Klagenfurt I’d done courses, but obviously being behind a desk is not the same as learning directly in the real world. I thought it would be much more useful, obviously also with the research in mind, to go to Ljubljana”. The publication of a competition for a scholarship from the (Italian) Foreign Ministry proved crucial; and so Dr. Fedel moved, lock stock and barrel, to the Slovene capital to start a new adventure whilst keeping to the theme of an analysis of the condition of women. So it was that in Ljubljana a new thread in her Euroregional experience was woven, leading her back to Italy, not in her own San Canzian on the River Isonzo but to Trieste.

“At first I got by using English but I soon realised that the courses I was following were insufficient. I was irritated that I was unable to understand everything, and it especially disturbed me that I had to have help to carry out the interviews necessary to complete the thesis. I carried on studying and after a few months I was finally able to speak and understand Slovene” she says. In the meantime however, her experience on a Ministry scholarship had come to an end, meaning she had to find paid work.

First came the experience as an assistant to Professor Langer at the University of Klagenfurt, but the distance Ljubljana and the Carinthian capital was too great to commute, even just for a few days a week. With too little money for a car, she began a search for a job in the place that would become her new home. Having to work within job quotas, given that at that time Slovenia had not yet entered the Schengen area, she decided to work to her strengths in order to carve for herself a place in the job market.

“In fact I was a student living in a foreign country – she explains – and my advantage was being able to speak Italian, whilst in the meantime, having picked up a good working knowledge of Slovene. It wasn’t particularly difficult to find part time job in an import-export firm, one in fact managed by an Italian, that also allowed me to teach in some private schools”. The experience gained allowed Serena to do a bit of “insider trading” at a management software company, where she was able to pass herself off, so to speak, (given that she was one) as a student needing to collect information to finish a doctoral thesis.

Even though Slovenia comes across, as it also does in her thesis, as a country where women enjoy the best working conditions, this does not mean that it is easy to find permanent work. Serena – who in the meantime was looking for a more secure position – came across an agency which seeks to place Slovene students in temporary jobs, positions reserved for those attending the University of Ljubljana. Serena decided therefore to follow two degrees at the same time, enrolling in a course for a degree in Political Science. Moving from job to job, in the meantime she finished the research and wrote up the thesis and finished the three year research doctorate, but wanted to stay in Ljubljana. “I didn’t want to return to Klagenfurt even if there would probably have been good opportunities to carry out new research work at the University, paid for with EU Interreg funds. “I liked (and continue to like) Ljubljana, it has that touch of Balkan spirit that makes it a warmer place than Klagenfurt. In addition it is also welcoming, on a human scale but you breathe a cosmopolitan air of a European capital. Obviously I also made a lot of friends in my months there. The only thing I missed was being close to the sea”.

The next step was to move on and look for a permanent job, this time not as a student, possibly in the area of Communication and Marketing. But the response is always the same: “At the moment we are not looking for staff but we’ll keep your file on our books” A series of C.V’s returned to sender – it wasn’t looking good.

Amongst the companies contacted however was a one in Trieste, the only one on the list and it was this one that replied, offering an eight month Apprenticeship in the Area di Ricerca. “By coincidence the company was involved in connectivity and security policies for company networks and was looking to expand into Slovenia and this was why my curriculum made its way to the top of the pile. There I worked as an apprentice before finding a job in a company that works in electronic commerce, but the most important thing to me is that I’ve moved to Trieste. I’ve been living here for a year and I like it a lot, the people are more open and I’ve had a chance to catch up with old friends”. But another move is on the cards, this time it would seem for good. Destination Cervignano (in the province of Udine) to work for a agricultural company.

“I would have happily stayed in Ljubljana. If I could– she reveals – I would choose to move there for good but my life has brought me back here and I’m happy about that. I’d do the whole thing again, making the same choices to end up exactly where I am today. And then there is balancing family and work time – returning to the theme of my doctoral thesis, which represents a problem here in the Region: and that’s why having as my boss the father of my children will prove a real advantage”.

Author: Annalisa Turel

Journalist with a degree in Public Relations she has worked for four years with the Italian daily Il Piccolo and other newspapers. Since January 2007 she has run GoriziaOggi, a daily blog supplying information on the Isontino, the territory on either side of the River Isonzo, running from Italy’s border with Slovenia to the Adriatic.